Gottfried Duden’s book A Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America inspired thousands to leave Germany for Missouri…

Why they Left

Webster’s Dictionary says “emigrate: To leave one’s own country in order to permanently settle in another.” Sounds simple enough. Just pack or sell everything that you own, cut all your ties with everyone you know, and ask all of your family members to do the same. Then on the faith of the words of a friend, relative or someone from your village who has gone before you, or maybe a perfect stranger, start out for a totally unknown place clear across the ocean where they speak another language, that you cannot even speak. You will risk your family’s lives on a dangerous ocean voyage, and potentially fatal diseases, and entrust your life savings in the hands of others. But you already know how desperate things are if you stay, where there is not enough food or land to raise crops to feed your family, and that each year the King continues to raise the taxes, and enact laws to serve his needs. Between 1785 and 1813, Germany was continuously at war, and young men were impressed to serve for a minimum of two years no matter what their family’s status was. As famine and disease spread, the crime rate grew. There were as many reasons to emigrate as there were Germans by 1824.

Why Missouri

Missouri original residents first settled along the major waterways of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers where there were abundant hunting grounds. French Canadian fur traders were joined by families from the east looking to carve out homes on the frontier as their fathers had. Many were from Kentucky, Virginia and Pennsylvania, and their fathers had served in the War against a British King, who had ideals similar to the German rulers. When soldiers from Hesse had been ordered to serve with the British army, many arrived only to be befriended by the colonists with whom they sympathized. The Hessians escaped and were smuggled to the western frontier where they soon blended with pioneers, with only their accents to betray their heritage. Historians have often commented that Daniel Boone’s maternal line of Morgan is suspected to lead to a German heritage as well. Several of the families that followed Boone into St. Charles territory were only one or two generations removed from Germany. Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1804. the U.S. set out to colonize the vast territory, offering land at beautiful prices. Timothy Flint’s biography of the famous frontiersman Daniel Boone, credited with leading pioneers to this el Dorado, was translated into German in the late 1780s.

Gottfried Duden

Gottfried Duden was born in Remscheid Germany in 1785, the son of a wealthy apothecary and his second wife, also of a wealthy upper class German family. When he was 6 years old his father died, leaving his widow the instructions that each child be given the best education. As his older brother would follow with the family business, Duden chose law for his profession. Precocious, and with a keen interest in literature, Duden began to study the United States and its westward movement at the same time as he listened to the stories of the poor Germans who faced him in his court room. In the early 1800s romance filled the air with love stories by Jane Austen and poems by Schiller and Keats, and music by Beethoven. This was the period of German Sturm und Drang, in which intuition and emotion was prized, rather than rationalism.

Duden laid plans to emigrate to the United States by 1819, but those plans were put on hold when a friend who was set to accompany him died. So in 1822 he published his first treatise Concerning the Differences of the States. Emigration books touting the charms of Britain, Russia and Brazil were rampant. But books on the U.S. advised against emigration, but Duden prevailed, feeling that only a book of first hand experience could be persuasive and reverse that trend. In 1824 he traveled to Missouri accompanied by his female cook and a young professional farmer he had recently met named Ludwig Eversmann who did not speak English. They lived with Jacob Haun, one generation removed from Germany, and with an understanding of the language likewise. Haun and his brother-in-law Dabney Burnett had assisted Duden in purchasing his land (north of the Missouri River directly across from today’s Washington) and establishing theirselves. Boone’s son Nathan who had surveyed the land as a U.S. Surveyor seven years before, also assisted Duden in learning about the area. Boone introduced Duden and Eversmann to area farmers, like his friend William Hancock. There Eversmann met his future wife, a sister to Hancock’s wife and Dr. Elijah McLean who lived across the river.

Duden lived in the area from 1824, establishing his own farm (Today’s Bethel Hills Community) by 1826, and writing a book of letters, in journal form, until 1827. When his plans for departure were announced, he made clear his intentions to return. When asked why he was leaving if only to return, he stated he had to return to publish his “Report” and let his fellow countrymen know what a “paradise” Missouri was. His 1500 copies of Report on a Journey of the Western States of North America was published in Bonn at his own expense in 1829. A wild success, copies were circulated and reprints published. Young Germans would take off for the American frontier by 1830.

Criticism of Duden’s Report began immediately. He replied defensively stating that his methods outlined were being totally ignored. Duden had stated that families of means should emigrate and settle together, reasoning that safety in numbers and the fellow familiarity would ease homesickness. He also stressed that ideally farming, such as the earlier pioneers, would enable them to provide well for their families. However, many of those “with means” would not be capable of that difficult lifestyle.

Baron von Bock and Dutzow

The first to follow Duden’s “outline for emigration societies” in 1832 would be the so-called Berlin Society, funded by the Baron J.W. Bock who later founded the village of Dutzow. His business partner and son-in-law Fredrick Rathje had come ahead with two Hutawa brothers, two Blumner brothers, and a few others. Upon arrival they met up with Augustus Grabs, an agent of Wilhelm Barez, a Berlin banker. They would find Bernard Fricke and the two Eberius brothers living across the river, in today’s Washington.

Duden’s suggestion of sending an agent ahead to investigate was well taken when families from the village of Soligen sent Herman Steines. He would advise his brother Fredrick to join him as soon as possible. Fredrick Steines would bring a group of 153 men, women and children and arrive in St. Louis in July of 1833. Despite the loss of his wife and three of his four children Steines still reported that “although everything here is not as Duden stated, in some ways it was better.” The Steines brothers settled in northeastern portion of Franklin County, and in 1839 established the first school in the area called Oakfield Academy.

By that time, letters were also being circulated in the Osnabruck area of Lower Saxony, with several families from that area booking passage on the ship Theodore Koerner and arriving in New Orleans. Among them were Karl Friedrich Meyer who had corresponded with Duden and carried his book, and a writer Friedrick Arends. Later the church history of St. Francis Borgia would state that also among that early group were 12 families who established that parish. Their names were Bleckmann, Buhr, Edelbrock, Husermann, Koehring, Riegel, Schmertmann, Schwegmann, Trentmann, Uhlenbrock, and Weber. This began a strong influx of emigrants from that area, resulting in many of the families in the Washington area tracing their roots from there.

The Giessen Emigrtion Society

Back in Germany, a young Lutheran minister Fredrick Muench corresponded with Duden, while his best friend and brother-in-law Paul Follenius visited him at his home. Both had been secretly involved in student revolution society at the University of Giessen. Gripped with emigration fever, Muench and Follenius wrote and published “A Call for Emigration” creating the most well established of German emigration societies, the Giessen Emigration Society. An agent was sent to investigate the area near Little Rock, and unfortunately did not return to report that the area would not do for their purposes until right before the date of their departure. Quickly, the meeting place was arranged for St. Louis, just as Follenius’ ship the Olbers departed for New Orleans, and arrived there on June 2nd.

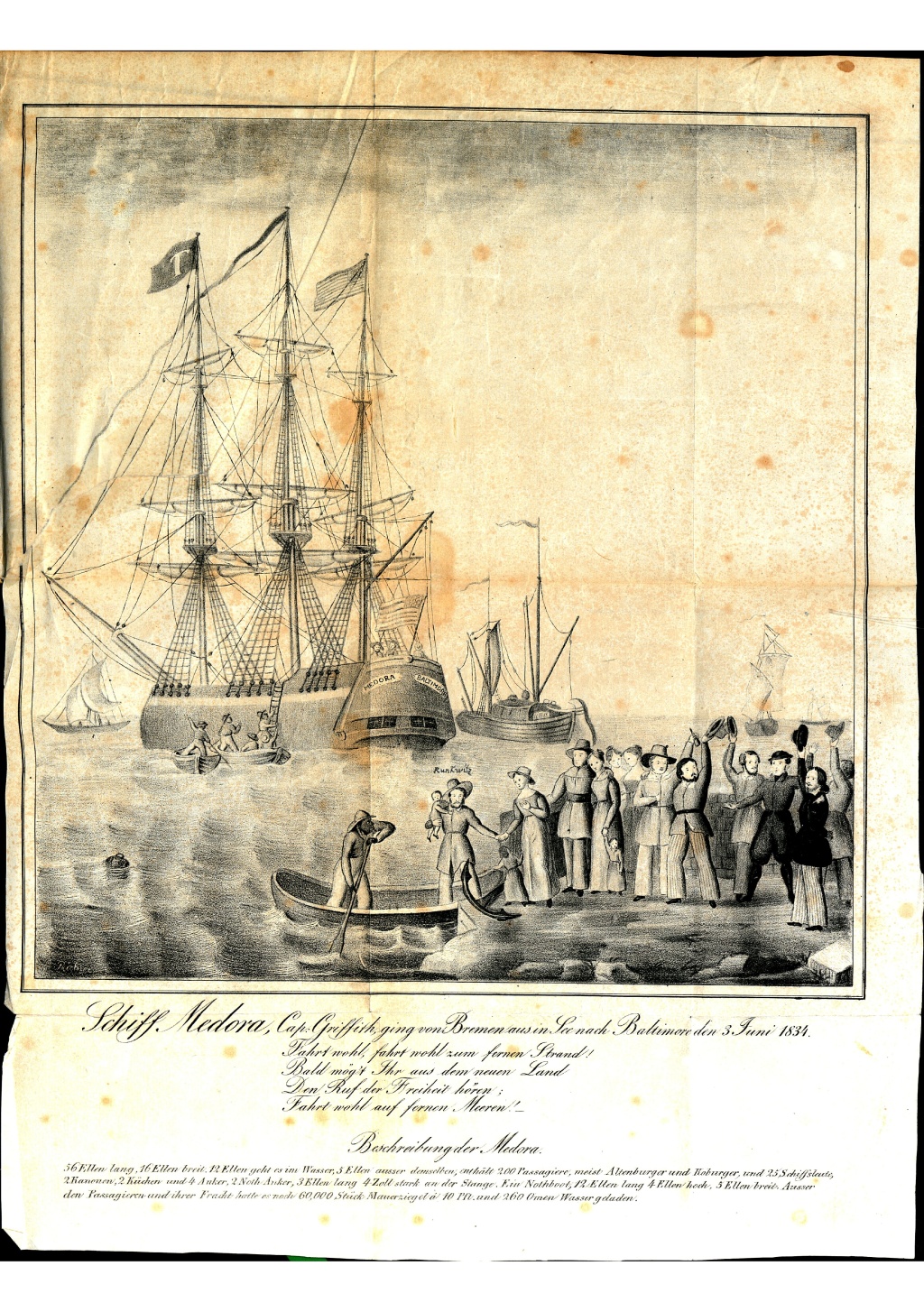

Little did they know as they headed for St. Louis that Muench and his group of 250 people were still in Germany. As the ship they had booked for Baltimore had yet to appear, they waited several days on the dock. Complaining to the shipping authorities about the costs involved in the delay of their departure, they were escorted to the island of Harriersand, and with only a cow barn for protection they were left to fend for themselves. They spent six weeks in the cramped quarters, with little food, waiting for a ship to Baltimore. Finally the Medora appeared and Muench arranged for their passage, and they would not arrive in the U.S. until the 24th of July!

By that time, Follenius’ party had started up the Mississippi, but many had fallen sick and the group stopped at Louisville. When they reached St. Louis they were surprised that Muench and his group hadn’t arrived. After waiting for days, they moved on to Dutzow near Duden’s farm, and purchased land in that area. As Muench’s group made their way west, they met Bock at Cincinnati on his way to Philadelphia. There Muench was shocked to learn that the disheartened group had abandoned their plan and scattered.

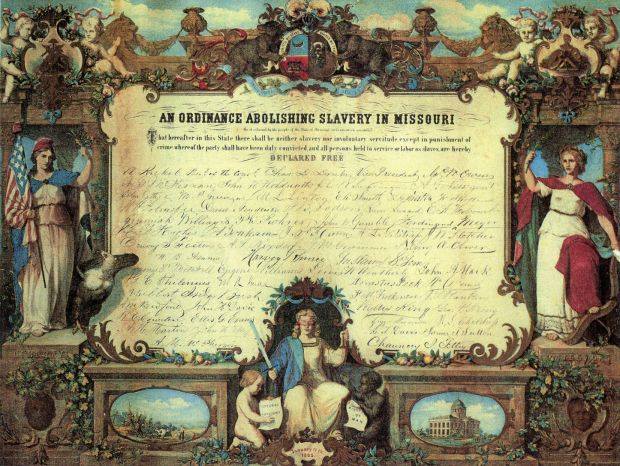

Although the idea of colonization and Utopian societies did not achieve what they hoped, they did manage to bring German emigrants into the area by the hundreds in just a few short years, causing it to be the core of German settlement in Missouri. Soon the counties of Warren, Franklin and St. Charles would be predominately German. Towns would spring up with the names of Holstein, Hamburg, Dissen and New Melle. An emigration society formed in Philadelphia in 1834 would culminate in the city of Hermann, Missouri by 1836.

Germans continued to come, as letters written home to friends and family of those early emigrants were read and shared after church on Sundays, published in the local paper, and passed from household to household. Word of mouth spread the news even faster, and those early Germans took a strong foothold on this area. When the Revolutions of 1848 created a second tidal wave of emigrants, they referred to those earlier emigrants as the grays, while the new and younger emigrants were called the “greens”. Gottfried Duden never did return to his farm on Lake Creek in Missouri. Instead he died rather bitterly in Bonn in 1856, never realizing what his “Report on a Journey” did for so many families in Missouri’s history.

You must be logged in to post a comment.