By the early 1800s, America’s ideals of freedom and democracy were spreading across Europe after its’ War of Independence. Napoleon was marching across Germany, when he was defeated in 1813. Two years of famine followed, soon famine, overpopulation and student revolutions. Germany was in turmoil, as the government executed those that spoke out. In Remscheid, an attorney named Gottfried Duden, felt that his fellow countrymen could find a better life in the United States, more particularly Missouri. Duden would arrive in St. Charles in October of 1824, and spend three exceptionally mild winters here. With a professional farmer and cook accompanying him, he spent his time visiting with many of the local residents, including the Zumwalt brothers and Nathan Boone. He said very little about the institution of slavery in his book, until almost the end. In 1829, he would return to Germany and published his emigration book “A Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America”. The book was just the right words at just the right time for many people.

In Germany Duden was mocked by the Government and labeled the “Dreamspinner” with tales of a “Garden of Eden” in an attempt to invalidate his writing. After all, how could there be this place where you elected your leaders, where you chose where you would live, your profession and your children could become educated and everyone could marry and practice the religion of their choice? In Germany you needed the governments permission to travel, to marry, even to move. The oldest would inherit the business or farm, and your religion was chosen by your ruler. Newspapers were censored, and those that spoke up were executed. Surely no one would believe there actually was such a place.

That first wave of Germans would be the beginning of change. Duden’s book would be the harbinger of that change. In the following decade, over 120,000 Germans would immigrate to the United States. One-third of those immigrants would choose Missouri as a destination, because of Duden’s book. And while one-fourth of them would set up shops in St. Louis, the rest would flood the Missouri River valley especially in St. Charles County and westward.

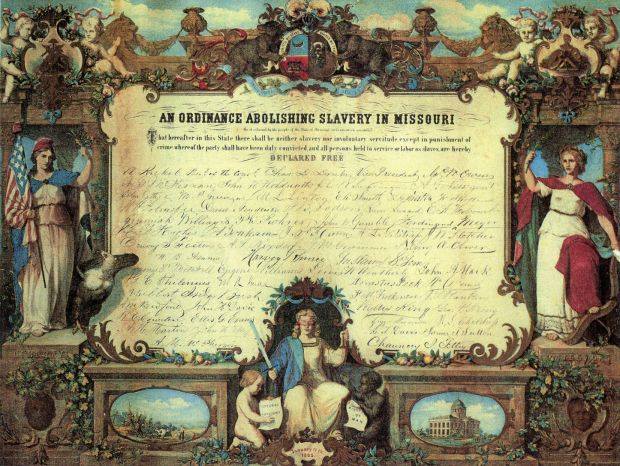

The arrival in Missouri of these German immigrants would have a tremendous impact on the people who were its’ African American residents. The Germans understood what oppression was, many have achieved passage to the United States as indentured servants, where their passage was paid, and they had sold themselves into servitude. By the 1840s, Missouri’s German immigrants were taking an active role in the government, and were raising their voices as abolitionists and speaking out against slavery. They had believed what our Declaration of Independence stated when it read “All men are created equal” and did not look about those enslaved as any less a man than themselves. They would risk their lives and their property to enable and assist enslaved people achieve their freedom, through the “Underground Railroad” hiding and helping them.

Archer Alexander was a fugitive slave hiding in St. Louis, who wanted his wife Louisa to join him. He paid a former neighbor $20, a German who lived nearby to help her on his way. William Greenleaf Eliot would share the story in his Archer Alexander – From Slavery to Freedom written in 1885…

The German farmer had kept his word. He had told Louisa that on Saturday evening, soon after sunset, he should be driving his wagon along the lane near her cabin, and that if they could manage to get down there, he would pick them up, and put them on the road. So at dusk they strolled down that way separately, without bonnets or shawls, so as not to attract notice. Nellie was thirteen years old, a smart girl, and well understood the plan. Meeting at a place agreed upon, they only had to wait two or three minutes before their deliverer came. He was driving an ox-team, his wagon being loaded with corn shucks and stalks loosely piled. Under these, arranged for the purpose, he made them crawl, and covered them up with skilful carelessness, so that they had breathing-place, but were completely concealed. He then drove on very leisurely, walking by the oxen, with good moonlight to show the way. When they had gone about a mile, one of their master’s family, on horseback, overtook them, and asked the farmer if he had seen “two niggers, a woman and a gal,” anywhere on the road. He stopped his team a minute, so as “to talk polite,” and said, “Yes, I saw them at the crossing, as I came along, standing, and looking scared-like, as if they were waiting for somebody; but I have not seen them since.” Literal truth is sometimes the most ingenious falsehood.

The man looked up and down the road, turned quickly, and went back to see if he could find the trace in another direction.

The farmer, chuckling to himself, drove on as fast as his oxen could travel, and before daylight was at the place where he had promised to bring his human freight. Archer paid him twenty dollars for his night’s work.

Missouri Germans Consortium Executive Director Dorris Keeven-Franke shared this and more story of the Underground Railroad on February 25, 2021. To watch the video recording of this presentation see…

Dorris Keeven-Franke is an award winning author, public historian and professional genealogist. She is the Executive Director of the Missouri Germans Consortium.

One response to “The Underground Railroad”

Thank you for this post. It was eye opening about how my German ancestors lived before coming here.

LikeLiked by 1 person